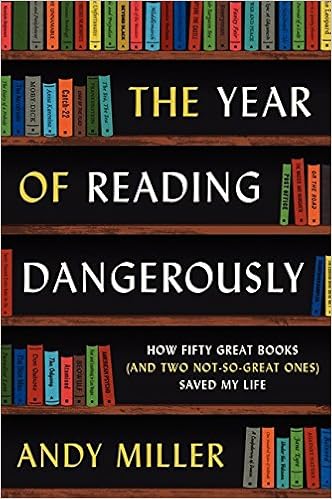

The Year of Reading Dangerously: How Fifty Great Books (and Two Not-So-Great Ones) Saved My Life

Andy Miller

Language: English

Pages: 352

ISBN: 0061446181

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

An editor and writer's vivaciously entertaining, and often moving, chronicle of his year-long adventure with fifty great books (and two not-so-great ones)—a true story about reading that reminds us why we should all make time in our lives for books.

Nearing his fortieth birthday, author and critic Andy Miller realized he's not nearly as well read as he'd like to be. A devout book lover who somehow fell out of the habit of reading, he began to ponder the power of books to change an individual life—including his own—and to the define the sort of person he would like to be. Beginning with a copy of Bulgakov's Master and Margarita that he happens to find one day in a bookstore, he embarks on a literary odyssey of mindful reading and wry introspection. From Middlemarch to Anna Karenina to A Confederacy of Dunces, these are books Miller felt he should read; books he'd always wanted to read; books he'd previously started but hadn't finished; and books he'd lied about having read to impress people.

Combining memoir and literary criticism, The Year of Reading Dangerously is Miller's heartfelt, humorous, and honest examination of what it means to be a reader. Passionately believing that books deserve to be read, enjoyed, and debated in the real world, Miller documents his reading experiences and how they resonated in his daily life and ultimately his very sense of self. The result is a witty and insightful journey of discovery and soul-searching that celebrates the abiding miracle of the book and the power of reading.

Fraud Fighter: My Fables and Foibles

Searching for Schindler: A memoir

Either I had already read them or I did not want to. Likewise, if you are unconvinced by a particular non-canonical choice, it was not an attempt to be unorthodox or provocative but simply intuitive – intuitive and honest. At a certain point, if I felt like reading The Silver Surfer, say, or The Epic of Gilgamesh, or something by Henry James, Julian Cope or Toni Morrison, I did so. There were no quotas. This selection of books, therefore, does not constitute a deliberate or alternative canon. If.

‘Jacob Marley’s Ghost’ and ‘Smike’ made themselves known, each expressing a few words of appreciation to their creator, seemingly oblivious to the desperate lives or afterlives he had bestowed on them. The sun shone, the audience applauded, ice cream was endemic. It was the best of times. It was hard to think of another author British people might celebrate in this manner; Shakespeare certainly, perhaps Austen or the Brontës, but that was about all. The British still love Dickens, even if they.

Not thinking about me what I am thinking about them. The atmosphere in Rare Books & Music, by contrast, does not make one feel as though one is being indulged in an embarrassing vice. People here read exemplarily. There is something uplifting about the conspicuous contemplation that seems to be taking place all around, so that even if one has come to do no more than read for pleasure – if such a thing is still possible – one feels oneself joining a noble communal endeavour. Much has been written.

See it as the mother’s job or because We’re Going on a Bear Hunt doesn’t have enough lesbians in it. Four out of five! I have to share toilet facilities with these losers. In the words of Eeyore the Donkey, which four out of five men may never know the joy of sharing: ‘“Pathetic,” he said. “That’s what it is. Pathetic.”’ Fig. 15: ‘Down Hole’, David Shrigley, 2007. (© David Shrigley) Tina has always said she could never have married a man who did not love books. Was she aware how reckless she.

About him, though it is very peculiar.’ So perhaps the lyricism I detected in Anna Karenina was the Maudes’ and not Tolstoy’s after all. But wait! Pevear ‘has never mastered conversational Russian’, notes the New Yorker, and it is his wife who actually speaks the language. I tell you, it’s a hall of mirrors. Fundamentally, there is probably no substitute for the original Russian; but unless we accept a substitute we don’t get to read Tolstoy at all. 2 At the performance I attended of Sunday in.