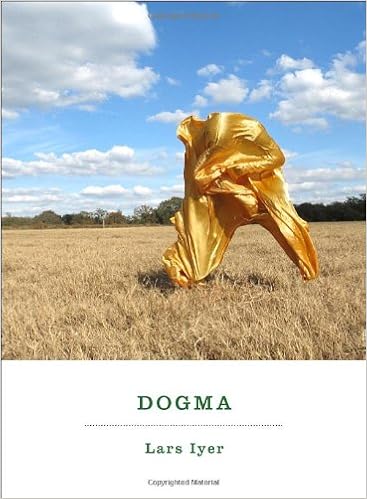

Dogma: A Novel

Lars Iyer

Language: English

Pages: 224

ISBN: 1612190464

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

A plague of rats, the end of philosophy, the cosmic chicken, and bars that don’t serve Plymouth Gin—is this the Apocalypse or is it just America?

“The apocalypse is imminent,” thinks W. He has devoted his life to philosophy, but he is about to be cast out from his beloved university. His friend Lars is no help at all—he’s too busy fighting an infestation of rats in his flat. A drunken lecture tour through the American South proves to be another colossal mistake. In desperation, the two British intellectuals turn to Dogma, a semi-religious code that might yet give meaning to their lives.

Part Nietzsche, part Monty Python, part Huckleberry Finn, Dogma is a novel as ridiculous and profound as religion itself. The sequel to the acclaimed novel Spurious, Dogma is the second book in one of the most original literary trilogies since Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable.

Devil's Consort: England's Most Ruthless Queen

Culture when he saw her memoir Hope Against Hope on my bookshelf. It didn’t matter to W. whether I’d read it or not, or whether I had any real idea of what it contained. The title itself must have excited me: that was enough for W. The title, and the myth of Mandelstam, exiled from his city and murdered in the Gulag: I had a feeling for that; what else could W. ask for in a collaborator, in these fallen times? Celan, in the midst of his walks, would phone his wife with the poems he had written.

From where the Luftwaffe came, and then, standing on a bench, pointing directly at the earth, where the bombs struck. I ask a passerby to take a photo of W. pointing at me, and of me pointing at W., and finally of W. and I pointing at one another. The Plymouth Gin cocktail bar. My working class credentials are far better than his, W. says over our Martinis. He is invariably moved when he thinks of me leaving school and working in the warehouse, and feels a great urge to protect and encourage.

How many times has he tried? How many emails has he sent? But it won’t get through, W. says. I won’t hear him. He’s resorted to blows, W. says, but it’s like beating a big, dumb animal. It seems pointless and cruel. How can I understand why I am being beaten? I bellow, that’s all. It’s perfectly senseless to me. He’s drawn pictures, W. says. He’s scrawled red lines across my work, but I have never understood; I’ve carried on regardless. No!, he writes in the margin. Rubbish!, he writes,.

Course. ‘It was part of the commonwealth, part of the open land we all shared’, he says. I’ve read Karl Polyani, W. says. I should know the argument: Capitalism began with the enclosure of land. It began as land was seized by the rich and the powerful. But for W., capitalism began long before that, he says. He evokes the virgin country which revealed itself as the ice sheet retreated, its shorelines stretching far out from where they lie now, joining our country to Europe, to continental.

Looks like Gary Glitter, post-disgrace, I tell him. I look like a thug, W. says. A monkey thug with great dangling arms.—‘Who could suspect you of any delicacy of thought?’, W. says. ‘You look like what you are. You can’t pretend otherwise’. What about him, then? Was Gary Glitter a philosopher? Did Solomon Maimon have a quiff? I should grow my hair, W. says. He’s always said that. He’s never liked my suedehead. But at least I’ve stopped wearing vests. W.’s seen the bags of vests in my flat, he.