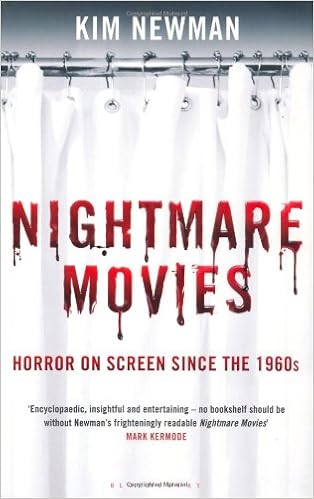

Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s

Kim Newman

Language: English

Pages: 633

ISBN: 1408805030

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Now over twenty years old, the original edition of Nightmare Movies has retained its place as a true classic of cult film criticism. In this new edition, Kim Newman brings his seminal work completely up-to-date, both reassessing his earlier evaluations and adding a second part that assess the last two decades of horror films with all the wit, intelligence and insight for which he is known. Since the publication of the first edition, horror has been on a gradual upswing, and taken a new and stronger hold over the film industry.

Newman negotiates his way through a vast back-catalogue of horror, charting the on-screen progress of our collective fears and bogeymen from the low budget slasher movies of the 60s, through to the slick releases of the 2000s, in a critical appraisal that doubles up as a genealogical study of contemporary horror and its forebears. Newman invokes the figures that fuel the ongoing demand for horror - the serial killer; the vampire; the werewolf; the zombie - and draws on his remarkable knowledge of the genre to give us a comprehensive overview of the modern myths that have shaped the imagination of multiple generations of cinema-goers.

Nightmare Movies is an invaluable companion that not only provides a newly updated history of the darker side of film but a truly entertaining guide with which to discover the less well-trodden paths of horror, and re-discover the classics with a newly instructed eye.

Bosses, who have built a housing development over a rural cemetery without bothering to shift the corpses. There’s a nasty EC comics story, ‘Graft in Concrete’, in which a bunch of crooked contractors do the same thing – the bodies crawl out of their graves and shove the crooks under a steamroller before embedding them in their own tarmac. Poltergeist’s supernatural complainants are more childish: a cyclone and a grumpy tree from the Wizard of Oz, and a fantasy land beyond the bedroom closet from.

1998). The controllers of a computer simulation of Los Angeles in 1937 suspect their own world is ultimately just as artificial (Josef Rusnak’s The Thirteenth Floor, 1999).1 A virtual reality designer is targeted by assassins within her latest creation, but her reality is also part of a game (David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, 1999). A novice industrial spy is a pawn in the master plan of arch-manipulator Sebastian Rooks, and discovers he actually is Rooks – his two separate identities are constructs.

Heroes who fight hard to tussle with a mystery only to learn that they are insane, dark shadows which evoke silent melodrama, and a use of restraints which parallels the contemporary torture cycle. Most typically, as in The Attic Expeditions or The I Inside, what we see through the eyes of madmen is not literally happening, though it’s ambiguous whether the patient (Adrien Brody) in The Jacket really is making periodic trips into the future. Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island (2009), from the novel.

Tangle of fractured family relationships breaking down over a fraught Christmas getaway, while West punctures the laddish self-confidence as a bunch of blokes assailed by harpie-like ‘zombirds’. The zombie plague was so widespread that there were even big budget studio entries. Francis Lawrence’s I Am Legend (2007), the third botched adaptation of Richard Matheson’s novel, impresses with its vision of the last man in New York (Will Smith) dodging zoo animals in the overgrown ruins of Times.

Shivers, Rabid, The Brood and Scanners even as it addresses again the morality of violent escapism and probes an uncomfortable merging of games strategy and narrative fiction. A psycho-drama with a heart of ice, Spider is also – as frequent allusions to webs and jigsaws attest – a puzzle, as we are slowly given information which enables us to distinguish truth from fancy. Spider (Ralph Fiennes), a long-institutionalised man, is released to a halfway house not far from the South London streets.