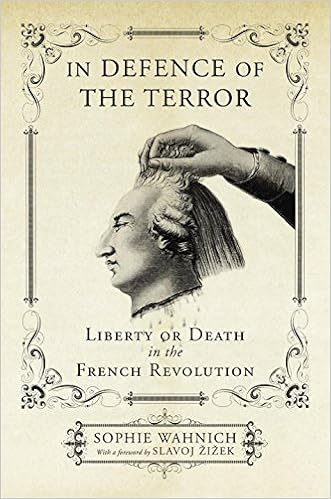

In Defence of the Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution

Sophie Wahnich

Language: English

Pages: 144

ISBN: 1784782025

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

For two hundred years after the French Revolution, the Republican tradition celebrated the execution of princes and aristocrats, defending the Terror that the Revolution inflicted upon on its enemies. But recent decades have brought a marked change in sensibility. The Revolution is no longer judged in terms of historical necessity but rather by “timeless” standards of morality. In this succinct essay, Sophie Wahnich explains how, contrary to prevailing interpretations, the institution of Terror sought to put a brake on legitimate popular violence—in Danton’s words, to “be terrible so as to spare the people the need to be so”—and was subsequently subsumed in a logic of war. The Terror was “a process welded to a regime of popular sovereignty, the only alternatives being to defeat tyranny or die for liberty.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Adbusters, Issue 103: #OCCUPYMAINSTREET

The New Yorker (March 14 2016)

Discontent and its Civilizations: Dispatches from Lahore, New York, and London

In Defence of the Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution

Generic figure of fright, and thus deadly. Far from presupposing an immediate response, it implies for those who feel it a high risk of demise. The question, ‘How was Terror put on the agenda?’ should thus be replaced by the question, ‘How was the dread instilled in the revolutionaries by their enemies overcome and transformed into the demand for terror?’ And beyond this, how was this demand was understood and accepted? And finally, what did the Terror found, or seek to found? * * *.

People in the hands of the legislators, in the sacred precincts of the Assembly, and to find their place there: ‘It is in your breast that the French people deposits its alarms, and that it hopes at last to find the remedy for its ills . . . We have deposited in your breast a great pain . . .’ The legislators had first of all to listen to the political pain of the people, to understand that this pain, if overcome, could produce anger, and then to re-translate this into the symbolic order so as to.

The one weapon we have against him to begin with and which we should be using, namely the economic tools of trying to make the economy even worse so that his appeal in the country and the region goes down . . . Anything we can do to make their economy more difficult for them at this moment is a good thing, but let’s do it in ways that do not get us into direct conflict with Venezuela if we can get away with it. The least one can say is that such statements give credibility to the suspicion.

Such conditions, is not a kind of terror (police raids on secret warehouses, detention of speculators and the coordinators of shortages, etc.), as a defensive countermeasure, fully justified? Even Badiou’s formula of ‘subtraction plus only reactive violence’ seems inadequate in these new conditions. The problem today is that the state is getting more and more chaotic, failing in its proper function of ‘servicing the goods’, so that one cannot even afford to let the state do its job. Do we have.

Details, like the decision to present the border between the territory held by the Roman army and the rebel territory, the place of contact between the two sides, as a lone access ramp on a highway, a kind of guerrilla checkpoint.6 One should fully exploit here the lucky choice of Gerard Butler for the role of Aufidius, the Volscian leader and Caius Martius’s (i.e., Coriolanus’s) opponent: since Butler’s greatest hit was Zack Snyder’s 300, where he played Leonidas, one should not be afraid to.